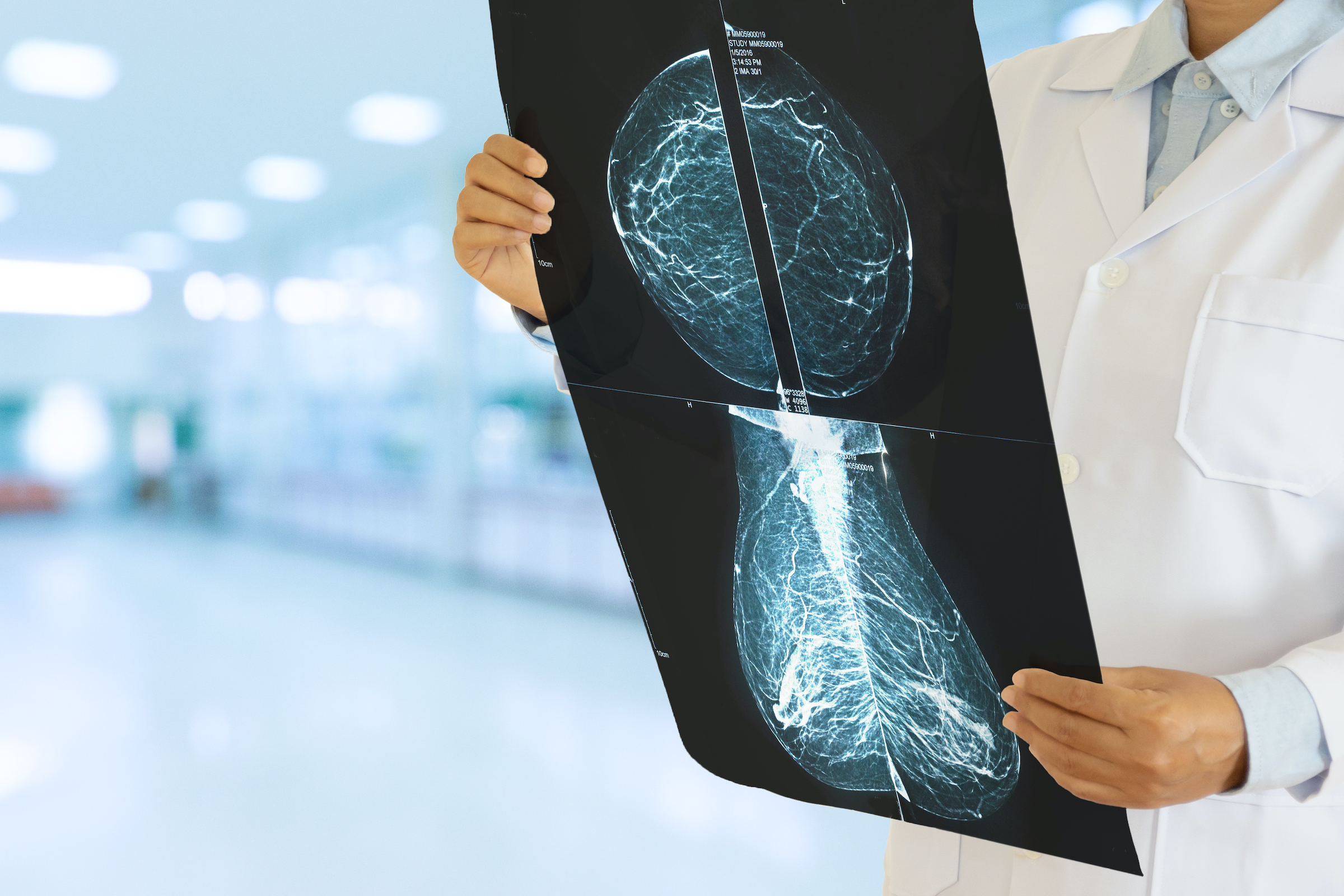

Pregnancy at younger age lowers risk of breast cancer by 30 percent

We spoke with experts and people diagnosed with breast cancer about the major causes of care-related financial

"The event of pregnancy itself changes how regions of DNA are open or closed. Think of a yo-yo. The centre of the yo-yo is what we call the nucleosome. It's a bunch of proteins that protect the DNA. When you release a yo-yo, you have a string, which represents that part of the DNA became open. And because it's open, now transcription factors can bind and either turn on or off genes. If you pull your yo-yo back, everything gets inside the yo-yo. That's what we call closed chromatin, so transcription factors cannot bind there."Pregnancy turns off the cMYC gene and turns on another set of genes that promotes senescence. Cells repeat the pattern open and closed DNA in subsequent pregnancies.Senescent cells "are in the grey zone, not growing or dying," says dos Santos. Depending on how the cells are pushed, they can either stay senescent, die, or grow too much and turn into cancer cells. "It's a very strong system, but you can mess up with it. And if you do mess up with it, that's when cancer develops. It allows us now to work on how we can keep those senescent cells from being perturbed."

Dos Santos and her team are currently working with human breast tissue organoids to see if human tissues act like those in mice. She's also transplanting cells altered by pregnancy into mice that have never been pregnant, in order to ascertain whether the altered cells can affect a non-pregnant environment. Both experiments suggest new drug targets. "This has opened up doors for us to further explore questions that have not been explored before," said dos Santos, such as whether puberty or ageing can prevent cancer the way pregnancy does.

.jpg)

My Medical Passport

My Medical Passport